Textile Stories 2: Paint Me Bare

Originally published in the artist book Generation, which accompanied photographic reliefs of these textiles

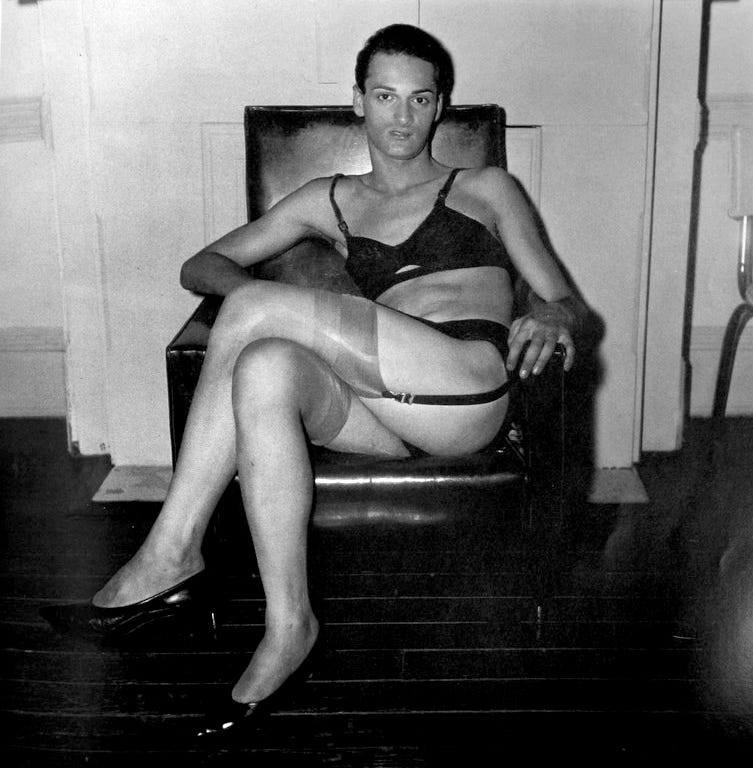

Clothing is a compromise between the fear of, and the desire for, nudity, which would make clothing part of the very process of neurosis, that is both display and mask… - Barthes, The Language of Fashion

In front of me is a tangle of 48 pairs of thigh-high stockings from the 1960s. Their colors seem drawn from a palette of earth tones, like shades of soil: soft, dry, fertile, rich—words not unlikely to be used when describing a woman. Tawny clay and taupe, deep russet browns that drift toward burgundy, dusky cocoa hues, cool charcoals and an occasional shot of milk white. Is each color meant to beckon to a specific person, or to paint her the shade of another? Even as a teenager, still obliged to wear these strange sheaths for special occasions, I never quite knew whether I was meant to choose a color that matched my skin or one I wished did. So, from the selection of shiny gold Legg’s eggs in the super market aisle, I would search for a true match and wonder who was represented by that spectrum of available hues—and who was excluded.

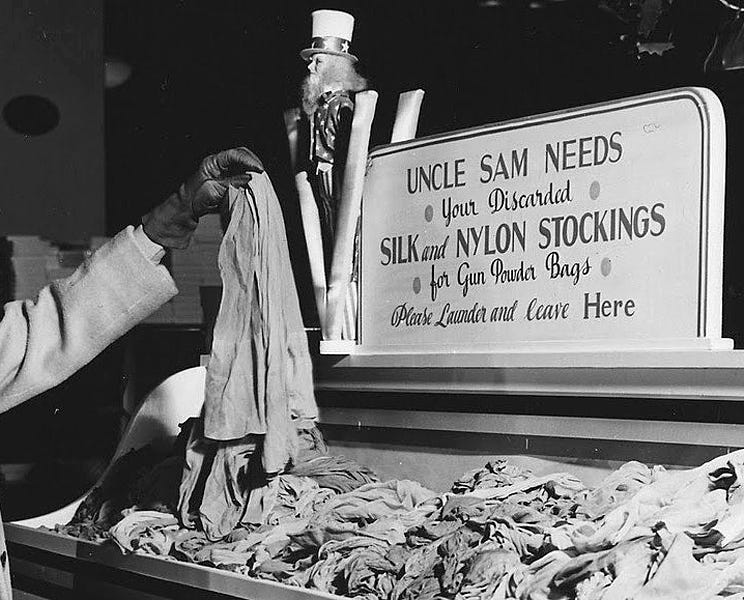

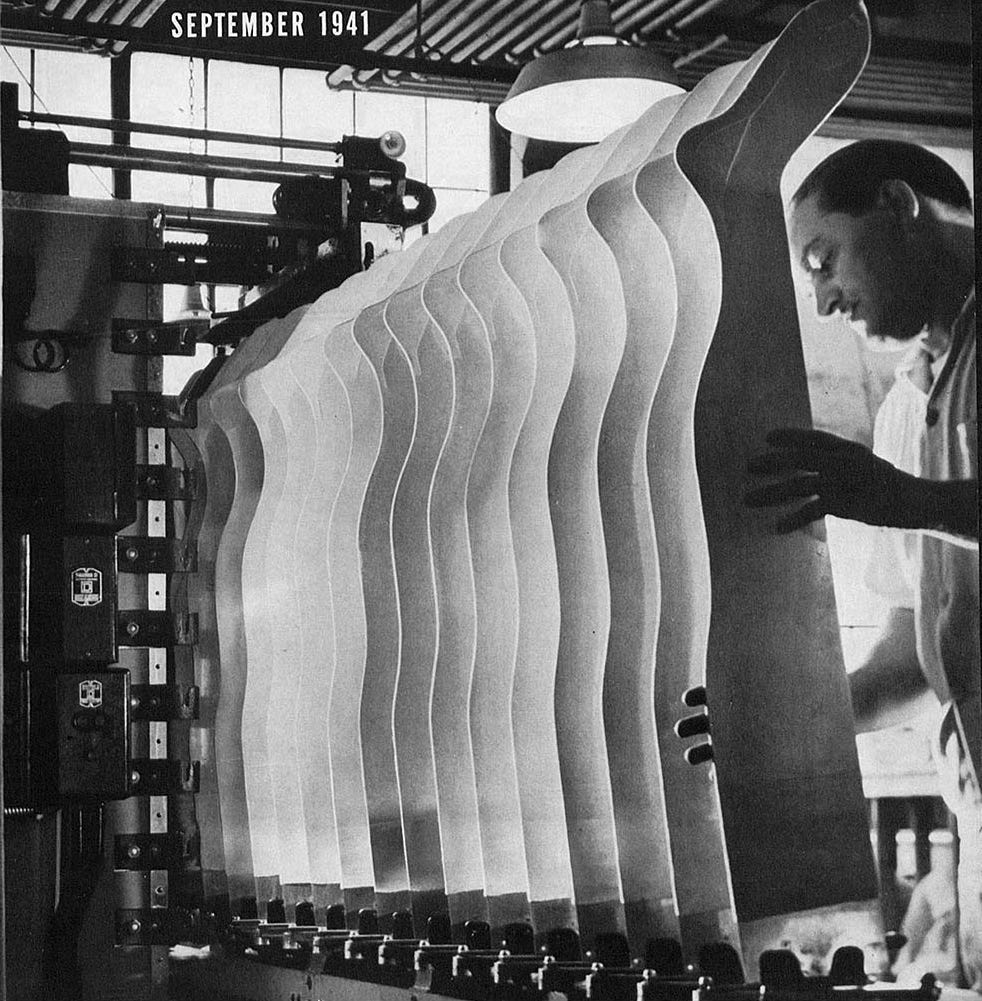

In 1939 DuPont Chemical Company released a new “miracle fabric” called Nylon. Stockings, which were previously silk, cotton and even wool, became ever more thin, diaphanous and resilient. They were more ubiquitous than ever before, but also more invisible. This new product coincided with World War II and the resulting unprecedented influx of women entering the American workforce beyond the domestic realm. These women were bridging two eras: one in which appearance (of both self and home) was paramount, and one in which function and modesty, for long hours of labor in public view, was a necessity. Stockings were touted as a veil of modesty and respectability while creating the illusion that we were bare (both “display and mask”). Charged with the absurd task of keeping us covered while making us appear naked, and most importantly, erasing our imperfections. We are taught to conceal, to embrace an illusion that is both our disguise and our armor. But there is a contradiction here, because any glance through twentieth-century advertising imagery, pornography, or even snapshots, reveal that it is the possibility of removing that mask, of disrupting that illusion, that is more titillating than either the mask or what is underneath it. There is apparently no end to the sex appeal and mystique of a removable skin, a layer that makes us smooth like dolls but can be shed to reveal the imperfect and storied texture of real human skin.